The exchange of letters, and more particularly the exchange of poems, had long played an important part in courtship in Japan. In the Heian period (794-1185) poetic exchange was the chief method of courtship, and this led to corresponding poems of lovers being part of the narrative in classic prose of this period, such as The Tale of Genji (Genji monagatari), and in major poetry collections still famous in the Edo period. Love letters played an important part in Kabuki plays, and they often feature in printed portraits, revealing something about the thoughts of the sitter.

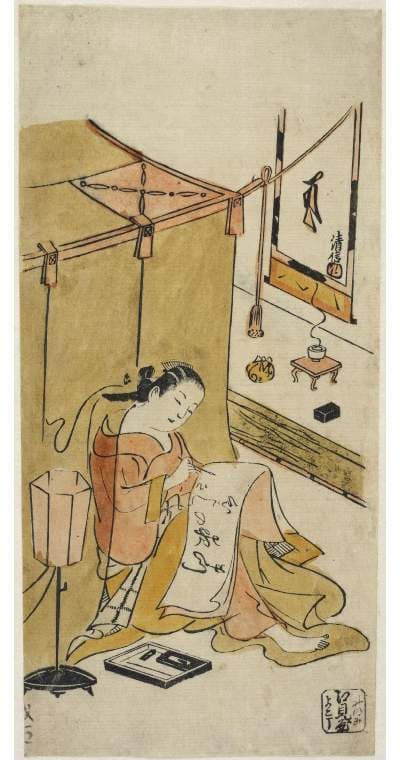

The night of longing Torii Kiyonobu I 1664-1729 P.84-2009

Woodblock print with hand colouring. Publisher: Emiya Kichiemon. Hosoban format. c.1710-20 Given by David Scrase to mark the 100th anniversary of the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum 2009

A courtesan is seated under the edge of a mosquito net around a bed, writing about the loneliness of a ‘night of waiting’ for her lover. It is not clear whether she is still expecting him to arrive, or writing a letter or a poem to express her longing during this lonely night. This is the only recorded impression of this print. It dates from the period before multi-block colour printing was developed, so the colour was added by hand with a brush to each impression of the print. The artist’s signature appears on the painted scroll in the background.

Although he worked in other subject matter, Kiyonobu focused almost exclusively on producing billboards and other promotional material for Edo’s Kabuki theatres, including the design of actor prints. He founded the Torii school of printmakers, which dominated the field of Kabuki theatre prints in the first half of the eighteenth century.

The love letter Rekisentei Eiri, active c.1790-1800 P.3513-R

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Unidentified publisher’s mark. c.1795-9 Given by T. H. Riches 1913

A young man hands a love letter to a woman wearing a bathrobe. Eiri’s work is relatively rare, and consists mainly of portraits of women dating from the 1790s and showing the influence of Utamaro. He also designed a series of famous lovers featuring characters from Kabuki plays.

Somenosuke of the Matsubaya

Matsubaya uchi Somenosuke

Kitagawa Utamaro, c.1753-1806 P.70-1960

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Wakasaya Yoichi. 1794.

Bought from the S. G. Perceval Fund 1960

From the series ‘Array of supreme beauties of the present day’ (Tôji zensei bijin-zoroe), which shows Yoshiwara courtesans three-quarter length against intense yellow backgrounds. Some of the designs were published with the word for ‘portrait’ (nigao) in the series title, before it was changed to ‘beauty’ (bijin). The courtesans only coincide in the annually published guide to the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter (yûkaku) for spring of 1794. Such prints capitalised on and promoted their celebrity status.

Somenosuke was a courtesan of the highest rank (yobidashi) in the brothel of Matsubaya Hanzaemon. She is shown opening a love letter with a hairpin. The daring design, pressing her against the edge of the print, emphasises her attempt to open the letter without anyone noticing, and keep its contents secret from someone outside the picture frame, presumably a client but possibly her colleagues at the brothel. The letter may be from a secret lover. Utamaro designed a full-length portrait of Somenosuke at around the same time as this one, and about two years later he portrayed her again in a bust portrait. Her child-attendants (kamuro) are named on this print as Wakagi and Wakaba.

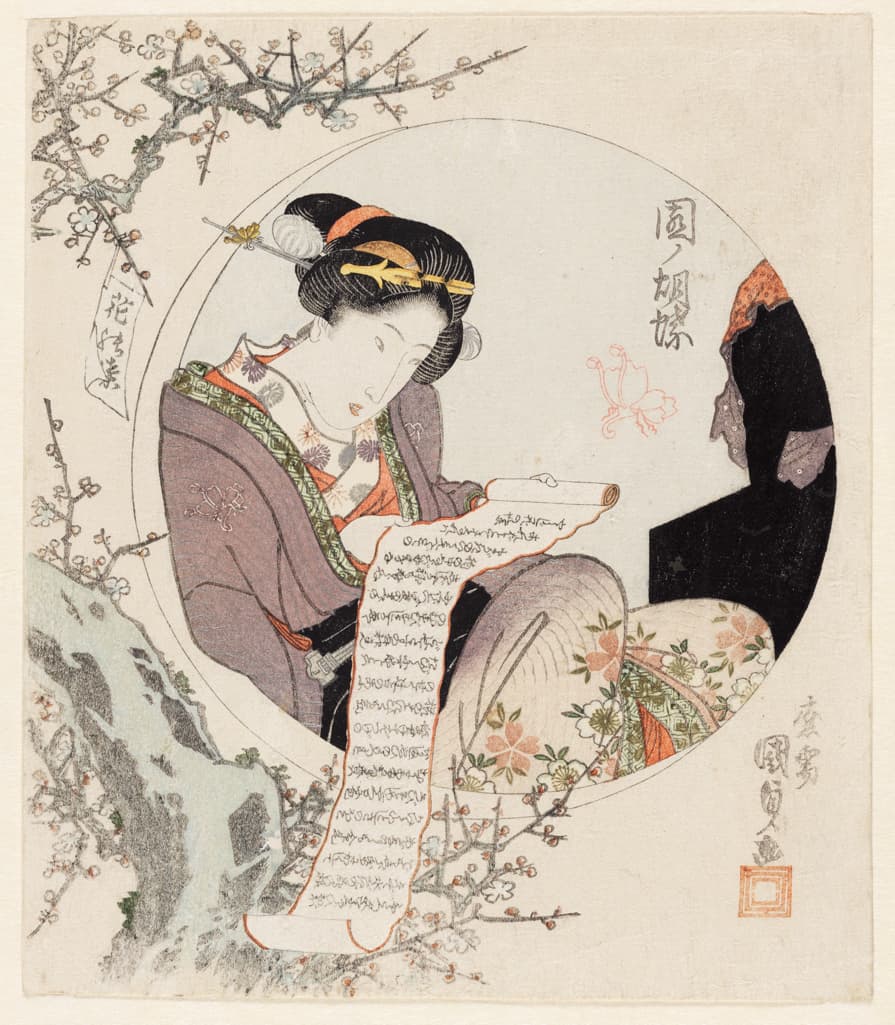

Butterfly on the flowers

Hana no chô

Utagawa Kunisada, 1786-1864, P.494-1937

Colour print from woodblocks, with metallic pigment, blind embossing (karazuri), and burnishing (tsuyazuri) on the black mirror and stand. Shikishiban format surimono. c.1823-5.

Given by E. Evelyn Barron 1937

A geisha is seated by a circular window reading a love letter. Her lover boasts of being literate in both Japanese and Chinese. He assures her of his love, heedless of the misfortune predicted by fortune-tellers and the fear of becoming the talk of the town. Nothing, he concludes, can prevent the two of them, he the butterfly and she the flower, from coming together, despite the many obstacles (‘hedges’) between them.

The detail of the scroll is remarkable; one character was corrected after printing by sticking over the top a new character on a tiny piece of paper. The text of the letter may be the lyric to a popular song by a poet using the name Sono no Kochô (‘Butterfly in the garden’), which appears on the print next to a red butterfly and blossom seal (repeated on the hairpin and kimono design). This seal seems to have been connected with a number of geisha and other female entertainers patronised by the feudal lord Môri Narimoto (1794-1836), who as a kyôka poet commissioned many surimono under a variety of pen-names. Sono no Kochô may have been the pen-name of Narimoto, or the name of the geisha herself.

Looking in pain: a prostitute of the Kansei Era

Itasô Kansei nenkan jorô no fûzoku

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1839-1892 P.1-2004

Colour print from woodblocks with textile printing (nunomezuri). Ôban format. Block-cutter: Wada hori Yû. Publisher: Tsunashima Kamekichi. 25/02/1888. Given by The Friends of the Fitzwilliam 2004

From the series ‘Thirty-two Aspects of Customs and Manners’ (Fûzoku sanjûnisô), showing women from different walks of life from 1789 to the 1880s.

The particular word used in the title of this print suggests that the woman is a low-ranking prostitute (jorô). Her hairstyle reproduces fashions of the Kansei era (1789-1801) as they appeared in the prints of Utamaro, although the use of square hairpins is anachronistic.

The woman is probably having the name of her lover tattooed onto her arm. To stifle the pain she bites on a handkerchief, a gesture usually seen in erotic prints (shunga) when a woman is stifling a cry of passion. The erotic overtones are reinforced by the glimpse of her red underrobe, and the displaced strands of hair. Her teeth are blackened with dye made from iron filings (ohaguro); this was usually the mark of a married woman in the Edo period, although prostitutes also blackened their teeth as a sign of adulthood.

The print may be a conscious echo of a well-known print by Utamaro, which shows a prostitute tattooing her name onto her lover’s arm.