In the Heian period (794-1185) exchanging poems was the chief method of courtship, and love dominated the famous poetry anthologies. The fabric of early fiction such as The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari) was woven from motives of love and desire. By the eighteenth century new forms of literature and drama had emerged as part of the ‘floating world’ culture centred on the pleasure quarters. The most popular-Kabuki theatre-combined revenge plots with stories of thwarted lovers, sometimes based on real life and often already made famous in earlier plays and books. Kabuki originated at the start of the Edo period (1603-1868) and developed into an elaborate stage spectacle with complex plots. The two main categories of plays were historical tales and contemporary domestic dramas. Even historical subjects derived from the puppet theatre or classical Nô drama usually included an amorous subplot set in the licensed pleasure quarter. Female roles (such as beautiful courtesans) had to be taken by male actors, usually female-role specialists (onnagata).

Books of ‘stories of the floating world’ (ukiyo-zôshi) were succeeded by satirical ‘books of wit and fashion’ (sharebon), which focused on the sophisticated connoisseur of the pleasure quarters (tsûjin). In the nineteenth century, a new wave of fiction aimed primarily at women readers brought a more sentimental approach. ‘Books to cry by’ (nakibon) and novels emphasising emotion and romance (ninjôbon), set a new trend towards romantic love. Illustrated novels (gokan) combined romance with the vendetta elements of Kabuki. In some cases classic love stories were updated and sensationalized; erotic versions went further, with implied sex scenes made explicit.

Sakyô no dayû Michimasa Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1797-1861

P.4-1980

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Ebisuya Shôshichi (Ebine). c.1840-2.

Given by Executors of R. F. Fortune 1980

No. 63 in the series ‘One hundred poems by one hundred poets’ (Hyakunin isshu no uchi), which illustrates poems from the well-known anthology One hundred poets (Hyakunin isshu) compiled in 1235 by the celebrated poet Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241).

Michimasa (992-1054) was a chief magistrate of the capital (Kyoto). He fell in love with Masako (or Tôshi), the Emperor’s daughter, who as High Priestess of Ise Shrine was expected to remain celibate. Their affair was in any case doomed because of their different social ranking. The composition of the poem was explained in the Goshûishû poetry anthology (1086):

‘He was secretly seeing someone who had returned from being High Priestess of Ise. He composed this poem when the court heard of this and posted guards so that he could no longer visit her, even in secret.’

According to the commentary on this print:

‘This poem laments the fact that the man would have liked to be able to tell the woman that their love is over and to tell her in person, rather than through a messenger. The feelings of this poem are indeed of deep sorrow.’

Kuniyoshi depicts Masako receiving and reacting to Michimasa’s poem, with its fateful message:

Now the only thing

I wish for is a way to say

to you directly

– not through another –

’I will think of you no longer!’

(translation: Joshua S. Mostow)

Some of the lead pigments in the print have blackened over time through exposure to contaminants in the air or in other pigments.

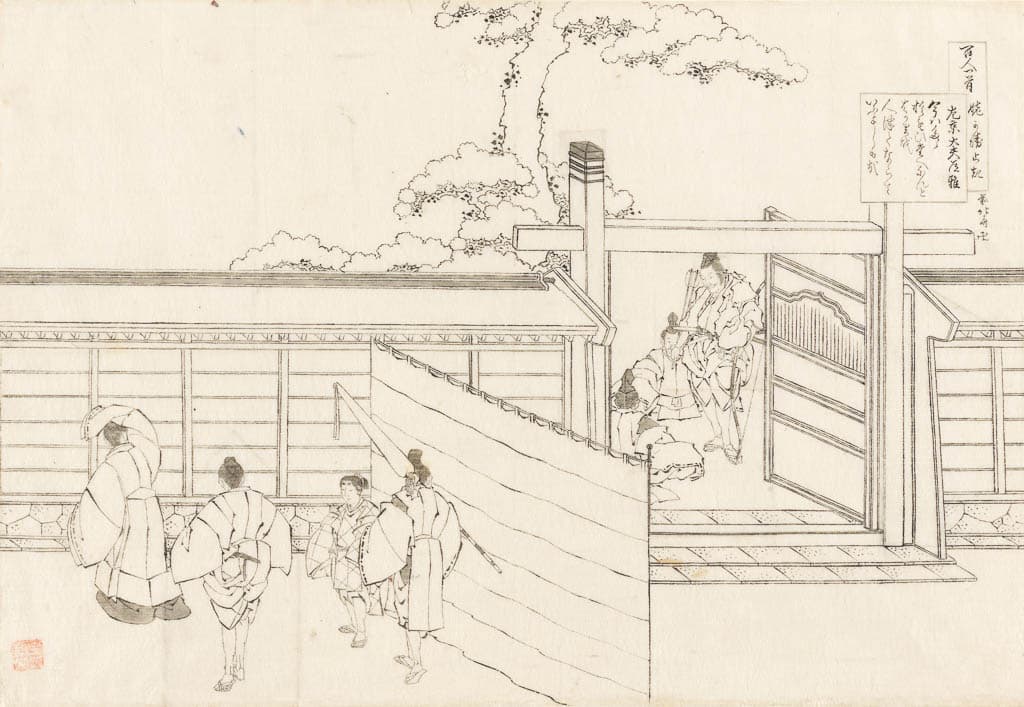

Sakyô no dayû Michimasa Katsushika Hokusai, 1760-1849

PD.3942-1937

Drawing in black ink (hanshita-e). Ôban format. c.1835.

Ricketts and Shannon Bequest 1937

This preparatory drawing was intended but never used for a print in Hokusai’s final series, ‘One hundred poems by one hundred poets as explained by a nurse’ (Hyakunin isshu uba ga etoki), begun in his seventy-sixth year. Twenty seven prints were completed before the series was abandoned around 1836, probably because of the crisis that hit Japan, involving crop failures and famine. Hokusai’s preparatory drawings for over sixty more subjects are known. If the print had been made, this final block drawing (hanshita-e) would have been pasted (or a copy of it pasted) face down on the woodblock as a guide for the block-cutter. The artist has inserted pieces of paper to alter the drawing in various places.

The print would have been no. 63 in the series, illustrating the same poem as Kuniyoshi’s print displayed alongside, but depicting a different scene. Hokusai shows Michimasa (on the left) with his servants outside Ise Shrine; on the right is the guard posted on the gate at the Emperor’s command to prevent the lovers meeting.

It is possible that Michimasa deployed a double meaning in the last line of the poem in case it got into the hands of the guards: they would read ‘I will think of you no longer!’, but if it reached Misako she would glean its second meaning: ‘I shall die of love!’

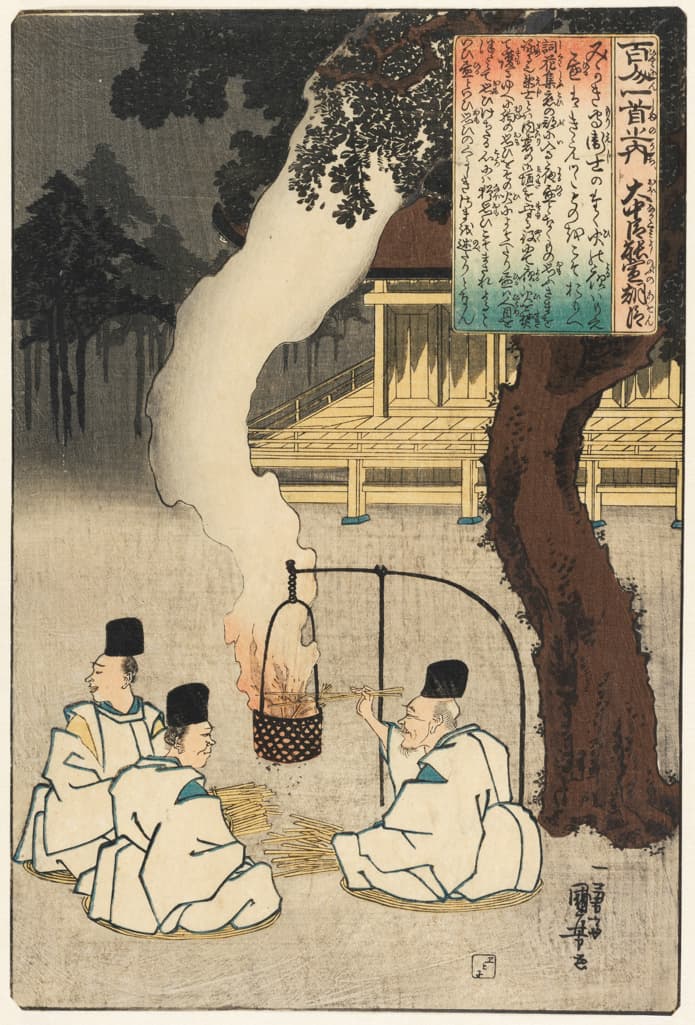

Ônakatomi no Yoshinobu no Ason Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1797-1861

P.3647-R

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Ebisuya Shôshichi (Ebine). c.1840-2.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

No. 49 in the series ‘One hundred poems by one poets’ (Hyakunin isshu no uchi), which illustrates poems from the well-known anthology One hundred poets (Hyakunin isshu) compiled in 1235 by the celebrated poet Fujiwara no Teika (1162-1241).

Ônakatomi no Yoshinobu (922-91) was one of the ‘Thirty Six Poet Immortals’. This poem does not appear in his own anthology of his works and may not be by him. The text accompanying the poem on the print states that it comes from the love section of the Shikashû anthology (commissioned in 1144) and explains that the verse means that the fire of the palace guards at night is like the burning desire of love. In the daytime people should hide their feelings from others, yet still the pangs of love will continue to grow and cause pain. The print shows three palace guards seated round a fire in a hanging brazier.

Like the fire the guardsman kindles,

guarding the imperial gates;

at night, burning,

in the day, exhausted,

over and over, so I long for her.

(translation: Joshua S. Mostow)

Komokata Hall and Azuma Bridge Komakatadô Azumabashi, Utagawa Hiroshige, 1797-1858

P.3568-R

Colour print from woodblocks with mica (kira). Ôban format. Publisher: Uoya Eikichi (Uoei). 01/1857.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

No. 62 in the series ‘One hundred famous views of Edo’ (Meisho Edo hyakkei), in the section for Summer. A view over the Sumida looking west, with part of Azuma Bridge visible on the left. In the foreground is the roof of Komakata Hall, a square temple housing an image of Kannon crowned with a horse’s head. The red flag signals the Hyakusuke cosmetics shop.

In the sky is a type of cuckoo (hototogisu), which was long associated in literature and art with the coming of summer in the fifth month, when it passed through the city on migration to the mountains.

The juxtaposition of the bird with Komakata Hall would have brought to mind a famous love poem by one of the celebrated courtesans named Takao, written to her departed lover as he made his way back to the city:

Are you now, my love,

near Komakata?

Cry of the cuckoo!

Her lover was reputed to be the lord of Sendai, whose affair with the courtesan Takao II was dramatized in Kabuki plays, such as The magic-lantern-shadow image of Date (Sono omokage Date no utsushie).

Fiction

Plum and painted shell

Komakatadô Azumabashi

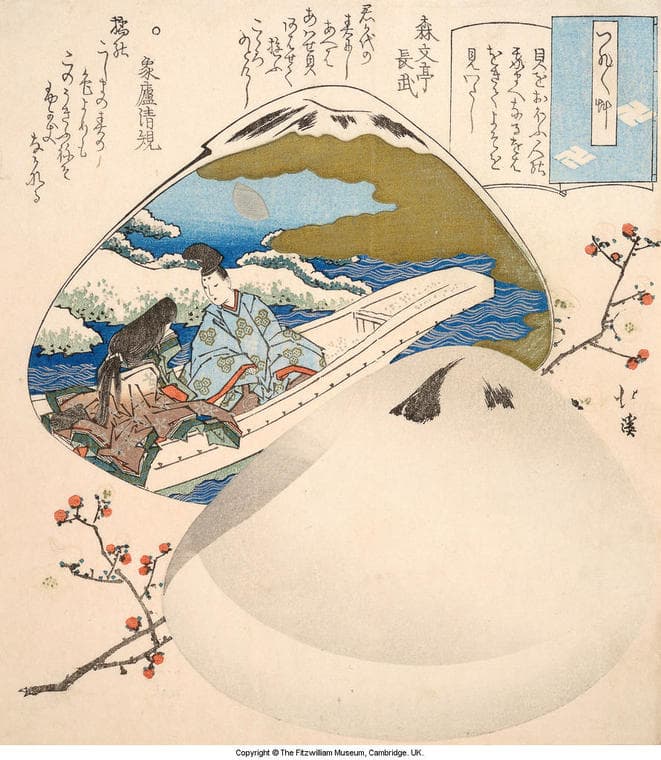

Totoya Hokkei, 1780-1850

P.370-1937

Colour print from woodblocks with blind embossing (karazuri) and metallic pigment. Shikishiban format surimono. Poets: Shinbuntei Nagatake, Kisaro Kiyonori. c.1830-4.

Given by E. Evelyn Barron 1937

From the series entitled ‘Essays in idleness’ (Tsurezuregusa) commissioned by the Manji poetry circle. The inscriptions include a quotation from chapter 171 of Tsurezuregusa, a prose miscellany written by Yoshida Kenkô in 1324-1331:

‘It happened once that a man playing the game of shell-matching took no notice of the shells before him, he was so busy looking to the side…’

Shell-matching involved pairing or reuniting poems or images painted inside the separated halves of shells. The scene in this shell is from the famous novel, The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari) by Murasaki Shikibu (c.973-1020).

Prince Niou has fallen in love with Ukifune (‘drifting boat’), mistress of his friend Kaoru. Disguised as Kaoru, Niou braves a journey through deep snow, reaching Ukifune at night. In this scene he takes her by boat to a house across the Uji River, with the moon in the dawn sky. Afterwards they exchange poems:

Niou:

Snow upon the hills,

ice along frozen rivers:

these for you I trod,

yet I never lost the way

to be lost in you.

Ukifune:

Quicker than the snow,

swirling down at last

to lie by the frozen stream,

I think I shall melt away

while aloft yet in mid-sky.

(based on a translation by Royall Tyler)

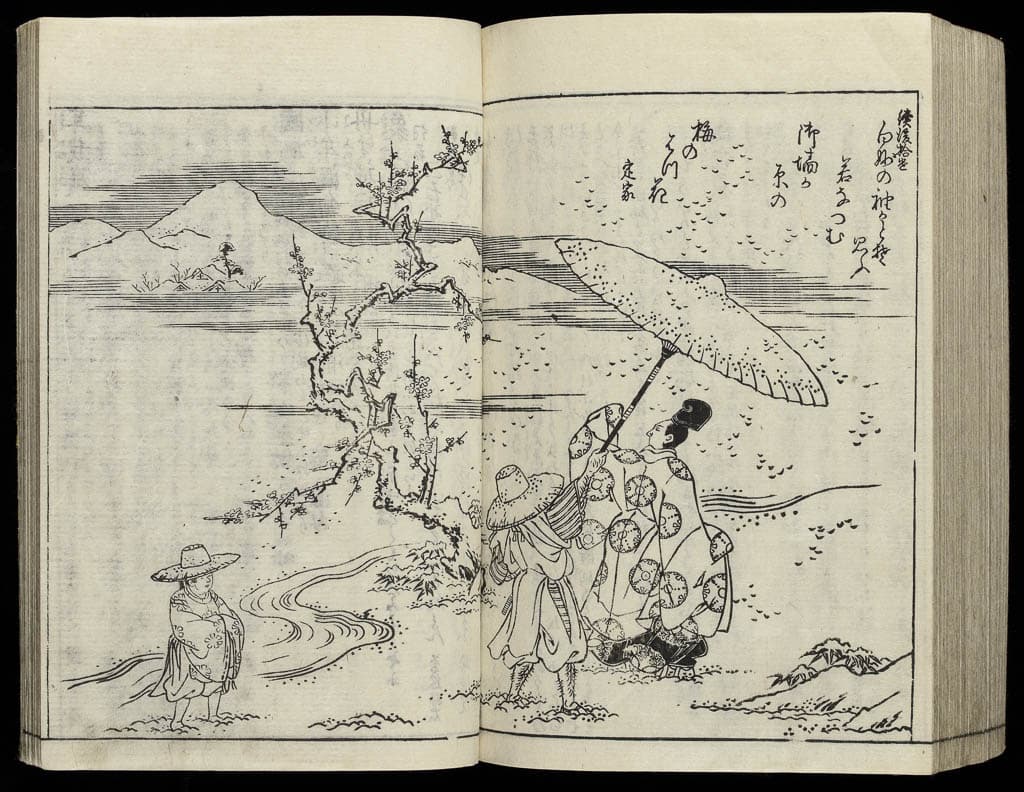

A bookcase of Edo-style kyôka

Azumaburi kyôka bunko

Kitao Masanobu (Santô Kyôden)

1761-1816

P.545-1943

Colour printed book from woodblocks, ôhon format, ‘bag’ binding (fukuro-toji), pink covers, printed title slips. Block-cutter: Seki Jiemon. Author of preface and compiler: Yadoya no Meshimori. Publisher: Tsutaya Jûzaburô. Edo, 1786.

Given by Louis C. G. Clarke 1943

The full title reads: ‘Newly carved in Tenmei [1781-8], one poem each by fifty poets: A bookcase of Edo-style kyôka (Tenmei shinsen gojûnin isshu: Azumaburi kyôka bunko). The book set a fashion for portraying living poets of humorous ‘crazy verse’ (kyôka) in comic parody of the conventionalized portraits of poets of classic verse (_wak_a) from the past. On the left page is the female kyôka poet Tamago no Kakujo, dressed in court robes and emerging from behind a folding screen that incorporates reed-blind panels, with her kitten − not yet tame − on a cord.

This is a visual parody of an incident in The Tale of Genji involving Genji’s wife, the Third Princess (Onna San no Miya), and her small Chinese cat, which ran out through the blinds onto the verandah, chased by a larger cat. Trying to escape from the tangle of its leash, the cat managed to lift the blind, giving a rare glimpse of the Princess to the young Kashiwagi, who was resting in the garden during a game of kickball (kemari): immediately he fell in love with the Princess. Unable to satisfy his desire for the Princess (at least not for another six years), Kashiwagi borrowed and kept her cat as a substitute.

Tamago no Kakujo’s name means ‘Square Egg’, from the expression, ‘a square egg and a sincere courtesan’ (two things you will never find); it is possible that she was a courtesan and that this was her pen-name for kyôka poetry. Her poem compares a woman’s changeable affections to trees that glow with colour or lose their leaves at random in the tenth month, when according to Shinto tradition the eight million gods of Japan left their shrines and congregated at Izumo Grand Shrine.

Vibrant then crumbling

without rhyme or reason,

a woman’s affections

are like leaves abandoned

by the gods in the tenth month.

(translation: Alfred Haft)

The illustration on the right-hand page shows the poet Hezutsu Tôsaku, whose kyôka poem does not relate to love and desire. But in showing him looking across at Tamago no Kakujo and holding a similar cat, the image alludes to Kashiwagi and the Princess’s cat, and the obsessive affection that he bestowed on it:

Soon it was no longer shy, and it curled up in his skirts or cuddled with him so nicely that he really did become very fond of it … ‘You I make my pet, that in you I may have her’ … he kept it to whisper sweet nothings to all by himself.

The Tale of Genji (translation: Royall Tyler)

Kunisada seems to have borrowed this visual idea in 1858 for his diptych print for the Asumaya chapter of Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji, referencing Kashiwagi and the Third Princess, in the series Lasting impressions of a late Genji collection (Genji goshû yojô). The visual reference to the incident of the Third Princess and her cat was popular in prints: for instance Utamaro design of c.1795, which echoes the composition of Masanobu’s portrait of Tamago no Kakujo.

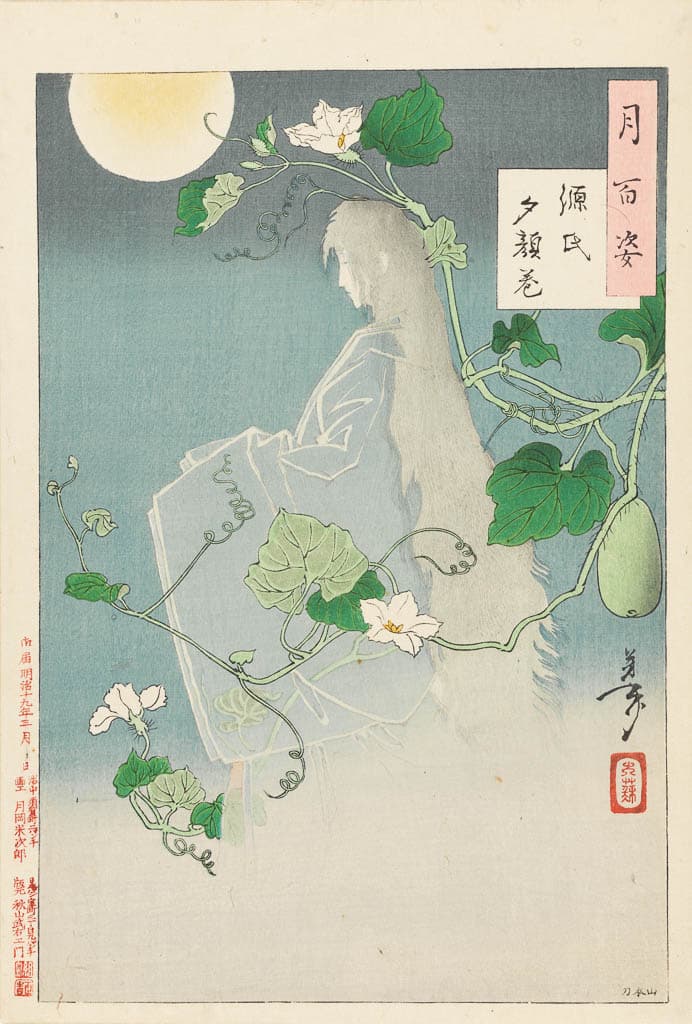

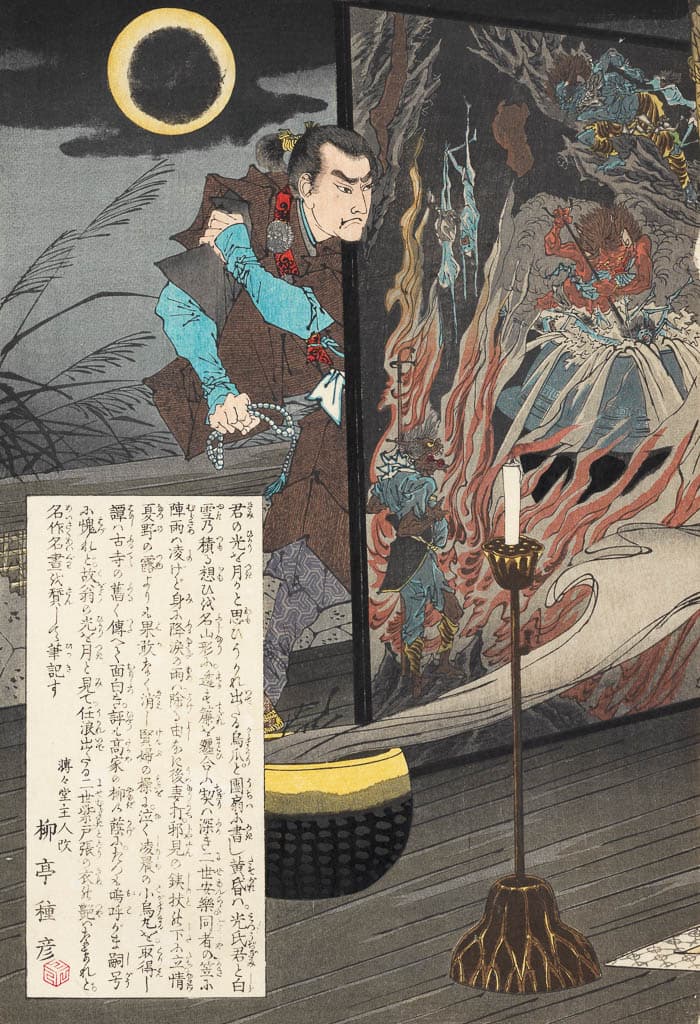

The Yûgao chapter from The Tale of Genji

Genji yûgao no maki

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

1839-1892

P.76-2004

Colour print from woodblocks, with blind embossing (karazuri) and textile printing (nunomezuri). Ôban format. Block-cutter: Yamamoto Shinji (Yamamoto). Publisher: Akiyama Buemon. 03/1886

Given by The Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum 2004

From the series ‘One Hundred Aspects of the Moon’ (Tsuki hyakkei) published in 1885-92.

This diaphonous figure is the ghost of the woman known as Yûgao, the most mysterious of Prince Genji’s lovers in The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari) by Murasaki Shikibu (c.973-1020). In Chapter 4, Genji is on the way to visit his old nurse when he notices the white flowers of a gourd vine overrunning the garden of a dilapidated house. He asks a servant to fetch a bloom and it is returned on a fan inscribed with a poem referring to his ‘evening face’, the literal meaning of the name of the flower yûgao (Lagenaria siceraria).

Genji courts the mysterious author of the poem, and takes her to a nearby villa, where they are visited in the night by the angry spirit of Rokûjo, Genji’s jealous lover. Yûgao breaks into a fever and within hours she dies. Genji is overcome with grief, and years later he still longed for a further glimpse of the woman who faded as quickly as the white flowers in her garden.

Yoshitoshi shows Yûgao’s spirit floating through her garden on the night of a full moon. The gourd flower was also known as ‘moonflower’, thus linking the subject to the theme of the series. Her lips are blue, a convention for the depiction of ghosts and corpses.

Rustic Genji

Inaka Genji

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi 1839-1892

P.18-2003

Colour print from woodblocks, with blind embossing (karazuri), textile printing (nunomezuri) and borderless shading (atenashi bokashi). Ôban format vertical diptych. Block-cutter: Negishi Chokuzan. Publisher: Matsui Eikichi. 20/08/1885.

Purchased from the Rylands Fund with a contribution from the Art Fund 2003

The title comes from Kunisada and Ryutei Tanehiko’s hugely popular illustrated novel (gôkan), Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji (Nise Murasaki inaka Genji), published in serial form in 1829-42. Tanehiko reinvented the eleventh-century novel, The Tale of Genji, in a fifteenth-century setting, with mystery story and plot-twists borrowed from the world of Kabuki theatre. The hero Mitsuuji was not only a heart-throb with a string of lovers, but used his philandering reputation as cover for investigating the theft of precious family heirlooms.

This scene comes from chapter 5, which alludes to the Yûgao chapter in The Tale of Genji see above

Mitsuuji’s lover Tasogare wears a robe patterned with the gourd or ‘moonflower’ that first drew Mitsuuji’s attention to her mother’s house. The lovers are fleeing across a desolate moor to escape her mother Shinonome, and spend the night in an old temple. Mitsuuji has wrapped a blind around them to stop his sword glinting in the moonlight. The government censor complained that the print was injurious to morals as it is impossible to see what Mitsuuji is doing with his other hand. Yoshitoshi is said to have responded that if everything is depicted, the flavour is lost.

Yoshitoshi evokes the uneasy mood of the novel, and includes details from Kunisada’s illustration. The atmosphere of the landscape is heightened by the subtle printing, especially the effect of the clouds around the bird and moon, which varies in each impression.

‘They began walking along a narrow path through deserted fields, pushing through long wild grass until they no longer knew where they were … Although the pure white moon shone brilliantly, a breeze began to blow, and they found themselves in a sudden rain shower … Mitsuuji tried to encourage Tasogare as much as he could, but he had never been on this path before, and he himself felt uneasy … Tasogare felt anxious about many things, but above all she worried about how far she had come with Mitsuuji and what might happen between them in the future…’

Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji

(translation: Chris Drake)

Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji

Nise Murasaki inaka Genji

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1839-1892

P.16-2003

Colour print from woodblocks, with blind embossing (karazuri), textile printing (nunomezuri) and gloss black (tsuyazumi). Ôban format triptych. Block-cutter: Horikô Noguchi Enkatsu. Publisher: Akiyama Buemon (Akiyama). 21/05/1884. Purchased from the Rylands Fund with a contribution from the Art Fund 2003

The title comes from Ryûtei Tanehiko’s serial novel Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji (Nise murasaki inaka genji) of 1829-42, which reset the classic eleventh-century novel The Tale of Genji in the fifteenth century, with a mystery storyline and theatrical plot-twists replacing the melancholy poetic tone of the original. In his attempts to track down stolen family heirlooms, the hero Mitsuuji sometimes manipulates his love affairs as a means to thwart his enemies, but he remains capable of sensitivity and deep feeling. This scene alludes to the Yûgao chapter in The Tale of Genji, see above

Mitsuuji (his robe decorated with the symbol of the Yûgao chapter in The Tale of Genji) and his lover Tasogare have now reached a dilapidated temple, where they are visited by a spirit purporting to be Mitsuuji’s jealous wife. Mitsuuji comforts Tasogare, but the woman returns as a wicked demon, intent on murdering Mitsuuji. Recognising the woman as her mother Shinonome, Tasogare slits her own throat. Shinonome follows suit. Mitsuuji announces that he knew all along that Shinonome had stolen the precious family sword. As she dies, Tasogare realizes that their love affair was a mere pretext to help Mitsuuji find the sword, but she is reconciled by his genuine grief and feeling.

Yoshitoshi conflates elements from several of Kunisada’s illustrations. On the left is an ascetic mountain monk (yamabushi) who attempts to exorcise the demon but turns out to be Kiyonosuke, the guard originally in charge of the stolen sword. The fish-shaped cartouche on the right alludes to the wooden fish that Kiyonosuke strikes to signal Mitsuuji’s men to approach. Shinonome wears the demonic ‘Hannya’ mask worn by the jealous spirit of Genji’s lover Rokujô (who is exorcised by a similar yamabushi in the Nô play Lady Aoi (Aoi no ue). It was Rokujô’s spirit that appeared to take Yûgao’s life in the corresponding scene in The Tale of Genji.

‘After they were alone again, Mitsuuji continued to comfort and encourage Tasogare in the abandoned guest room. It must have been past midnight. A strong wind was blowing, and they could hear the rough soughing of many pines. The weak, low voice of an owl made them feel even lonelier. Then the woman’s shape appeared again. She was a demon woman now, and she kicked her way through the sliding doors, which were painted … She waved her horns, which were like gnarled old branches, and in one hand she held an iron pole. Her eyes bore down on the two.’

Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji

(translation: Chris Drake)

Illustrated famous places in Yamato

Yamato meisho zue

Takehara Shunchôsai

active 1772-1801

P.3692-R

Printed book from woodblocks, ‘bag’ binding (fukuro-toji), yellow covers, printed title slips. Author: Akisato Ritô Meshimori. Publisher: Takehashi Heisuke (Shonoya). Osaka, 1791.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

An illustrated gazetteer to the province of Yamato (modern Nara Prefecture). This page is part of the description of Kumedera temple and illustrates the story of Kume, an eremite living in ancient times. Through Taoist methods Kume became transcendant, achieving the power of flight. Seeing below him a woman washing clothes, his mind was clouded with desire and he fell from the sky, losing his powers. He married the woman, but later regained miraculous powers to help with the building of Kumedera temple. This illustration shows the woman rinsing the locally grown potato-like taro, rather than washing clothes.

‘Nothing is more likely to lead a man astray than sexual desire. What a foolish thing a man’s heart is! For a lovely fragrance is ephemeral, as we all know, and the heady incense of a woman’s garments soon fades. Even so, the whiff of an exquisite perfume will always set a man’s heart racing. Similarly, Kume the Transcendent lost his mystical powers when he caught sight of the seductive whiteness of the legs of a maiden who was washing clothes. This was understandable, for the sleek plumpness of her flesh and limbs left nothing to the imagination!’

Yoshida Kenkô, Essays in idleness (Tsurezuregusa), c.1330

(based on a translation by Money L. Hickman)

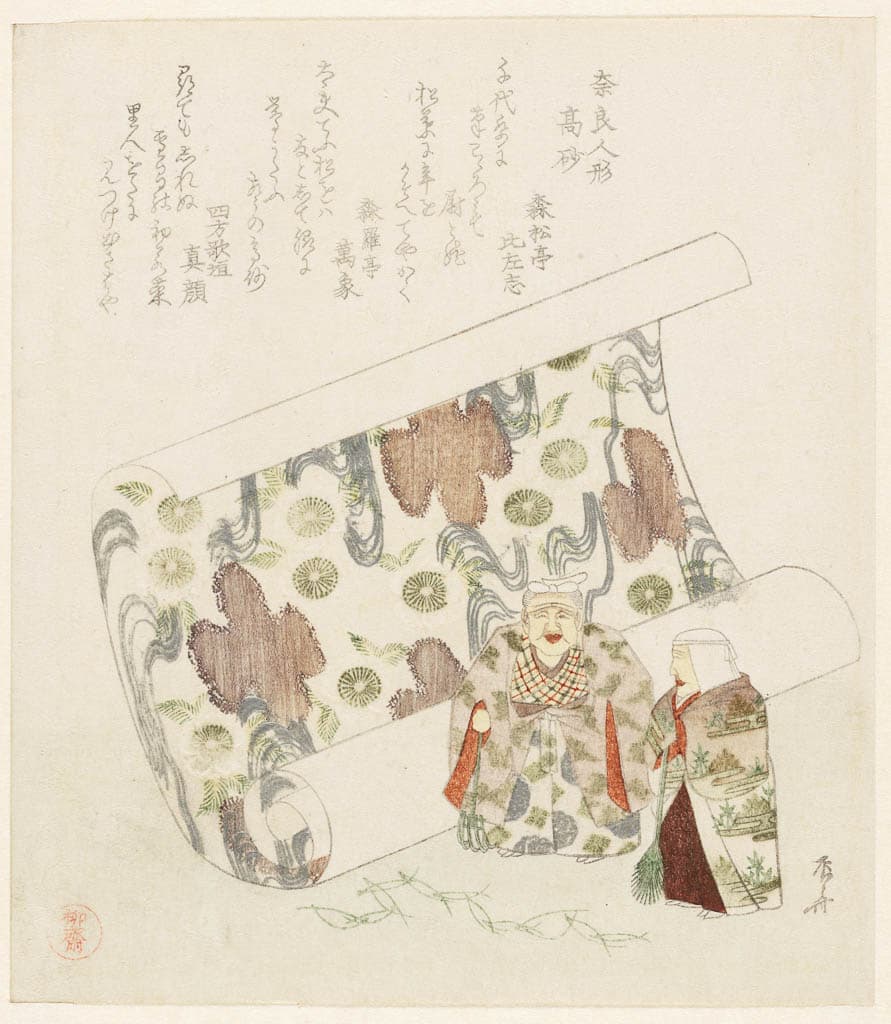

Still life with Jô and Uba

Ryûryûkyo Shinsai

active c.1799-1823

P.66-1938

Colour print from woodblocks with metallic pigment, blind embossing (karazuri) and fabric printing (nunomezuri). Shikishiban format surimono. c.1820.

Given by E. Evelyn Barron 1938

Known as the Eternal Couple, Jô and Uba fell in love when young, and after living to a very old age their spirits came to abide in pine trees, one on Takasago beach in Harima, and the other at Sumiyoshi in Sesshô near Osaka. Their spirits returned on moonlit nights in human form, Jô with a rake and Uba with a broom, to continue clearing pine needles on Takasago Beach. The evergreen pine needles, like the love of the Eternal Couple, symbolise longevity, a common theme for surimono given or exchanged at New Year.

Shinsai pioneered still-life surimono and concentrated on them to a greater degree than any other designer. Here he depicts dolls of the Eternal Couple, holding a rake and broom, with pine needles scattered in front of them. Their garments and the scroll behind them are decorated with elements alluding to Takasago Beach.

Drama

The actors Ichikawa Danjûrô VII as Jô and Segawa Kikunojô V as Uba

Utagawa Kunisada

1786-1864

P.480-1937

Colour print from woodblocks with metallic pigments. Shikishiban format surimono. Producer’s seal: Surikô Kozen. c.1823-5.

Given by E. Evelyn Barron 1948

These figures holding Nô masks come from a Kabuki play based on the Takasago legend famous from a Nô play. Known as The Eternal Couple, Jô and Uba fell in love when young, and after living to a very old age their spirits came to abide in pine trees, one on Takasago beach in Harima, and the other at Sumiyoshi in Sesshô near Osaka. Their spirits returned on moonlit nights in human form, Jô with a rake and Uba with a broom, to continue clearing pine needles on Takasago Beach. As the second poem on this print makes clear, evergreen pine needles, like the love of the Eternal Couple, symbolise longevity.

Tinged the colour of mists

that surround Mt Hôrai,

isle of the immortals,

this couple flourishes

at the dawn of spring.

– Sansuitei Kiyoshi

Wrinkle-like ripples

of the male and female waves,

will buffet these shores

for countless ages, just as the love

of Jô and Uba remains evergreen.

– Ifukutei Miyamori

(translations: John T. Carpenter)

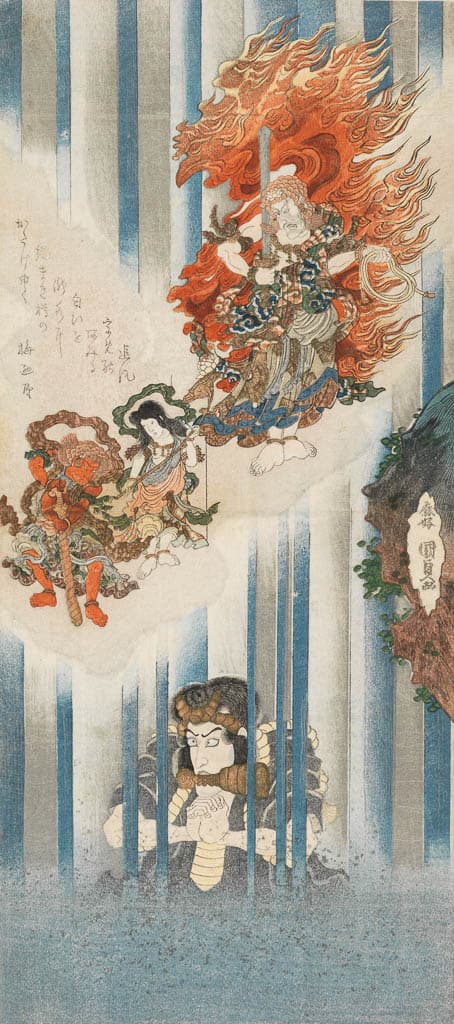

Ichikawa Danjûrô VII as Mongaku and Ichikawa Danjûrô V (top) as Fudô Myôô

Utagawa Kunisada

1786-1864

P.507-1937

Colour print from woodblocks with metallic pigments and blind embossing (karazuri). Shikishiban format surimono, vertical diptych. Poet: Umenoya. c.1832.

Given by E. Evelyn Barron 1948

The thirteenth-century chronicle Tales of the Heike (Heike monogatari) tells how the monk Mongaku recited prayers at the base of Nachi waterfall in mid-winter to atone for the unintentional murder of the woman he loved. After a week he lost consciousness until he was revived by the Buddhist deity Fudô Myôô and his child attendants Kongara and Seitaka.

Before becoming a monk, Mongaku was besotted with Kesa Gozen. She rejected his advances, and in a desperate strategy to preserve her honour, she persuaded him to kill her husband whom she then impersonated so that she was murdered in his place. Numerous Kabuki plays were based on this story, but this is an ‘imaginary grouping’ of Danjûrô lineage actors, rather than a record of an actual production. The scene had special significance for the Danjûrô lineage of actors since their founder Danjûrô I prayed successfully to the image of Fudô at Shinshôji temple in Narita. Before assuming the Danjûrô stage-name, actors performed the same religious purification as Mongaku at the waterfall at Shinshôji, where it was believed that the spirit of Fudô came to inhabit them. A votive plaque painted by Kunisada at the temple also records this scene.

The poem on this print by Umenoya plays irreverently by associating Fûdo’s coiled rope with the rope used to wrap wine casks as temple or shrine offerings, and by transforming the penitential waterfall (taki) into a famous brand of wine-Takisui-meaning ‘water from a waterfall’. This brand was sold at the Yomo wine shop in Izumichô in the Kanda district of Edo.

Sawamura Tanosuke II as Ashikage Yorikane and Onoe Matsusuke II as the courtesan Takao

Utagawa Toyokuni

1769-1825

P.619-1991

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format vertical diptych. Publisher: Suzuki Ihei. Publisher’s approval seal: Yamashiroya Toemon. 1813.

H. S. Reitlinger Bequest 1991

The story of the retired feudal lord (daimyô) Ashikaga Yorikane and the courtesan Takao derived from an historical incident in 1741 involving lord Date Tsunamune of Sendai, who did have an affair with a courtesan named Takao, but did not murder her. Feuds involving the Date family featured in several Kabuki plays, with names changed and the action set further back in time. This print was published in association with the performance of The magic-lantern-shadow image of Date (Sono omokage Date no utsushie) at the Nakamura theatre in Edo during the third month of 1813, which featured these actors in these roles.

This is the famous sagehiri, or ‘hanging from the crown-of-the-head’ scene. Yorikane has fallen in love with the courtesan Takao and when he comes to suspect that she is continuing an affair with a former lover, he flies into a jealous rage. Suspending her over the side of a boat, he drops her into the waves by slicing through her hair with his sword.

This scene was a sensational hit with the audience, and the performance depicted on this print may have been its first on the Kabuki stage, adapted from a similar scene in the puppet theatre.

The actor Sawamura Tanosuke usually played women’s roles, but in this production he played the male lead because it was especially associated with the Sawamura school of actors. His performance was acclaimed, but the actor playing Takao was better known for playing the role of a dandy, and this foray into female impersonation was not well received. Toyokuni may also have drawn inspiration from an illustration of this incident in the book Illustrated story of the golden flower (Ehon kinkadan) by Hayame Shungyôsai, published in 1808.

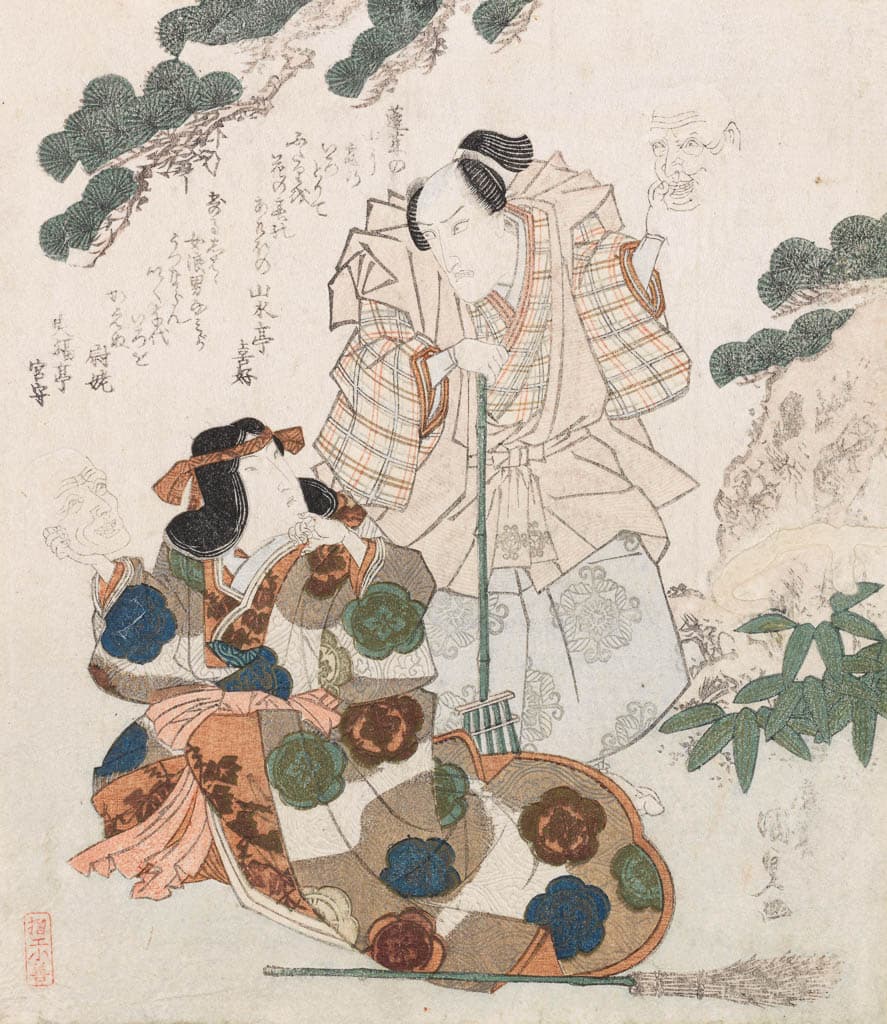

Onoe Kikugorô III as Izutu-ya Dembei and Iwai Kumesaburô II as Oshun Ichikawa

Utagawa Kunisada

1786-1864

P.479-1937

P.478-1937

Colour print from woodblocks with metallic pigments and blind embossing (karazuri). Shikishiban format surimono diptych. Poets: Ryukaen Mizugaki and Ryuôtei Hananari. c.1832.

Given by E. Evelyn Barron 1937

This scene of lovers meeting under a plum tree in a rain storm illustrates the play Scapegoat Oshun (Migawari Oshun, or Hanakawado migawari no dan), which was performed with these actors in 07/1827 and 10/1832. Judging from the form of Kunisada’s signature, this print was probably made to commemorate the 1832 performance.

Oshun’s lover Dembei has been entrusted with finding and killing Oshun’s lord, so she decides to make the sacrifice of killing herself in place of him. As a first step, when she meets her lover Dembei on a dark night in the rain, she pretends that her love for him is over. This is the scene depicted in this print.

The poems on the print quote dialogue from the play:

’I still feel my passion even though

I gave up loving you…’ (right sheet)

’Love changes just as easily as the

current in the River Asuka…’ (left sheet).

Numerous Kabuki plays featuring Oshun and Dembei were adapted from plays originating in the puppet theatre, which were based on a real event that took place in Kyoto in 1703: the double or love-suicide, along the Kamogawa river, of the rice merchant Dembei and Oshun from Horikawa.

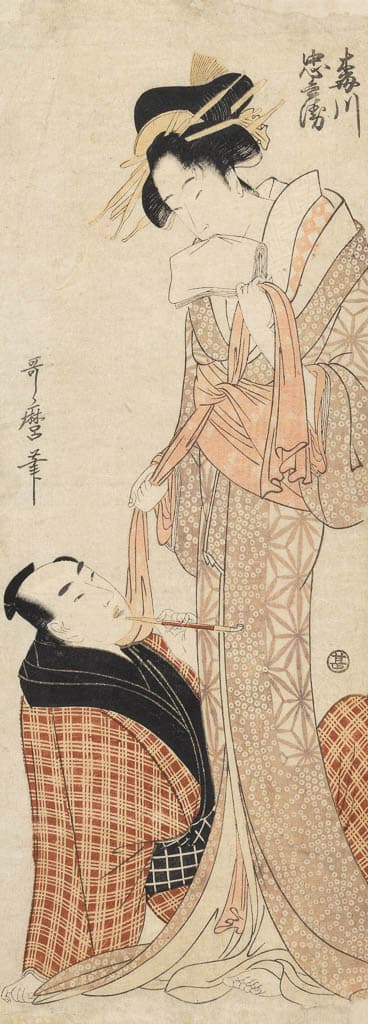

Umegawa and Chûbei

Kitagawa Utamaro

c.1753-1806

P.201-1946

Colour print from woodblocks. Naga-ôban format. Publisher: Maruya Jimpachi. c.1800.

Oscar Raphael Bequeast 1941 (received 1946)

One of four tall (naga-ôban) format prints by Utamaro published by Maruya Jimpachi around 1800, all featuring famous lovers from puppet plays.

Numerous Kabuki and puppet plays featuring Umegawa and Chûbei derive from The courier of Hell (Meido no hikyaku), written by Chikamatsu Monzaemon in 1711. It was based on real events in Osaka in 1710, when the courier Chûbei was executed after using official money entrusted to him to buy out the service of a courtesan named Umegawa. In the play his motive for using his customers’ money to buy out her contract is to save her from another suitor. They run away to the village where he was born in Yamato Province, intending to commit ‘love-suicide’. Continuing into the mountains on foot, eventually they die from cold in the snow.

Prints usually depicted the lovers escaping to commit ‘love-suicide’. This is more erotic. Umegawa ties or unties her lower sash (obi), trailing it against Chûbei. In an echo of the gesture seen in erotic prints when women stifle cries of passion, she grips in her teeth the tissues used to mop up after sex. This may be a reference to the play in which Chûbei’s mother is puzzled as to why he is using up so many tissues: ‘How can he blow his nose so much?’

Kabuki actors Sawamura Sôjûrô III (left), Segawa Kikunojô III (centre) and Kataoka Nizaemon VII (right)

Katsukawa Shun’ei

1762-1819

P.317-2013

Colour print from woodblocks. Hosoban format triptych. Published by Enomotoya Kichibei. c.1795.

Given by the Friends of the Fitzwilliam with the aid of the V&A Purchase Grant Fund 2013

The play depicted is probably Five great powers that secure love (Godairiki koi no fûjime), performed with this cast at the Miyako theatre in Edo in 01/1795. It was based on events surrounding a real-life mass murder in the Sonezaki Shinchi brothel district of Osaka in 1737. A first version of the play was produced in Osaka in 1792, but after its author Namiki Gohei moved to Edo at the end of 1794 to write for the Miyako theatre, he rewrote the play for an Edo audience, relocating the action from Osaka to Edo’s unlicensed pleasure quarter, Fukagawa.

‘Five great powers’ (Godairiki) was a Buddhist invocation referring to the five bodhisattva of Osaka’s Sumiyoshi Inner Shrine. It was the practice among Osaka geisha and courtesans to seal love letters with these three words, invoking the power of the bodhisattva to ensure that the letter would arrive, safe and unopened in the hands of the intended. It then became general practice among women to write ‘Five Great Powers’ on shamisen, hairpins and other personal valuables as a sign of fidelity.

The plot involves a love triangle between the geisha Koman (centre), Gengobei, a strait-laced samurai retainer (left), and Sangobei, a villainous retainer (right). Gengobei is persuaded by Koman to pose as her lover to put off the unwanted advances of Sangobei. This leads to Gengobei’s disgrace, but by this time Koman has fallen in love with him and severs her finger as a token of her love. They become lovers. Gengobei asks her to get close to Sangobei to see if he has a stolen family heirloom.

In league with Gengobei’s brother, Sangobei tells Koman that they will kill Gengobei unless she ends her relationship with him. Gengobei does not believe Koman’s letter of ‘divorce’ until he sees that the inscription ‘Five great powers’, which she inscribed on her shamisen as a pledge of love to him, has been altered (actually by Sangobei) to read ‘Beloved Sango’. Furious, Gengobei stabs Koman and cuts off her head before reading her letter explaining her true feelings and identifying Sangobei as the thief of the heirloom.

Prints usually depicted the ‘divorce’ scene with the shamisen, but here Shun’ei probably depicts the earlier scene when Koman and Gengobei first pretend to Sangobei that they are lovers.

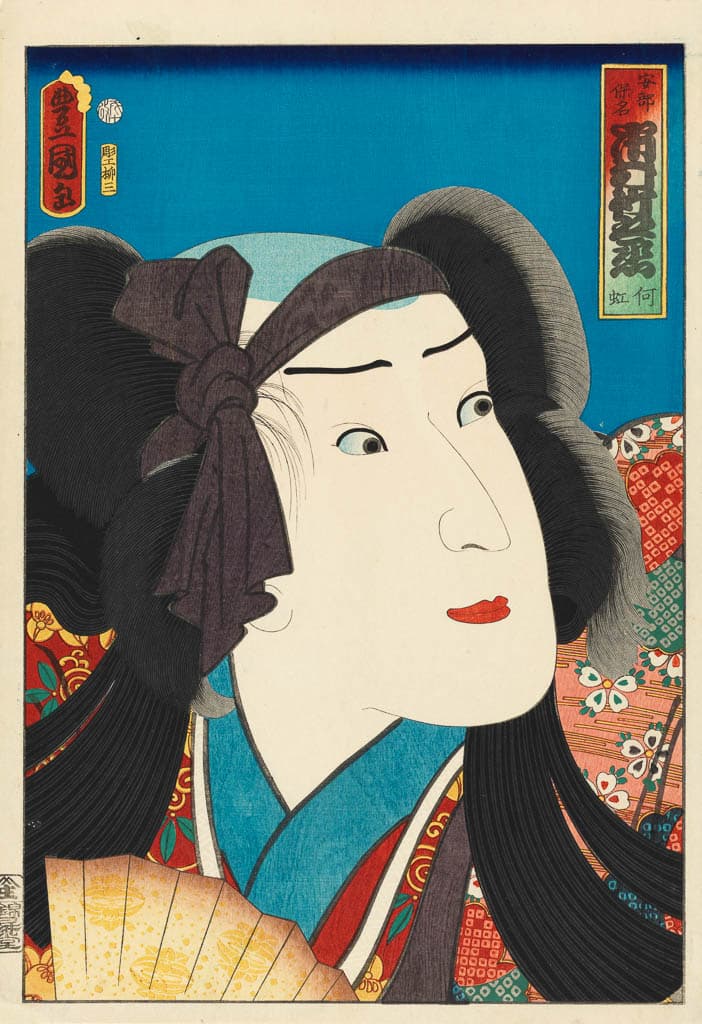

Ichimura Takenojô V as Abe no Yasuna

Utagawa Kunisada

1786-1864

P.90-1999

Colour print from woodblocks with blind embossing (karazur_i) and fabric printing (_nunomezuri). Ôban format. Block-cutter: Horikô Ryûzô. Publisher: Ebisuya Shôshichi. 10/1862.

Given by The Friends of the Fitzwilliam with the aid of the MGC Purchase Grant Fund and the National Art Collections Fund 1999

From an untitled series of large-head portraits (okubi-e) of Kabuki actors made in the last years of Kunisada’s life, employing the most expensive materials and the finest block-carvers and printers. It was recognised by his contemporaries as his masterpiece. All of the featured actors performed during Kunisada’s lifetime.

Ichimura Takenojô V (1812-51; his poetry name Kakô is also given on the print) was known for his refined features (as well as a taste for saké and luxury) and he was therefore well suited to the role of Abe no Yasuna, which required the actor to perform as a gentle, romantic male lead of the type called nimaime. Printed portraits like this celebrated and promoted Kabuki actors as superstars.

This scene comes from Act II of the play A Courtly Mirror of Ashiya Dôman (Ashiya Dôman Ôuchi Kagami) first performed in 1734. In 1818 it also became the subject of an independent dance named ‘Yasuna’. When the position of diviner at the imperial court is denied to him, Yasuna’s betrothed takes her own life in despair and he himself goes mad with grief at her loss. Plagued by visions, he wanders through the spring countryside in search of her, ‘his form drifting senselessly, his hair dishevelled’, as he carries her brocade robe over one shoulder. The purple headband is a stage convention indicating illness or mental distraction.

Hôrin Temple Moon: Yokobue

Hôrinji no tsuki - Yokobue

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi

1839-1892

P.23-2003

Colour print from woodblocks, with blind embossing (karazuri) and textile printing (nunomezuri). Ôban format. Publisher: Akiyama Buemon. 12/1890

Purchased from the Rylands Fund with a contribution from the National Art Collections Fund 2003

From the series ‘One Hundred Aspects of the Moon’ (Tsuki hyakkei) published in 1885-92.

Yokobue was an attendant of empress Kenreimonin in the twelfth century. A young guard fell in love with her, but when his father objected to the match he left to become a monk at Hôrin temple in the mountains. Yokobue travelled to see him, but fearing that he might be tempted to forget his vow, he made use of the fact that he had changed his name and sent a message that no one of the name she was calling was at the temple. Heartbroken, Yokobue departed.

According to the thirteenth-century chronicle Tales of the Heike (Heike monogatari) she became a nun, but another version of the story in the sixteenth-century Book of Yokobue (Yokobue sôshi) states that she threw herself into the Ôi River and her lover then ran down the mountain to find her drowned.

The print shows her turning away from the temple, with the mood of the landscape reflecting her state of mind, and a pair of intertwined pine trees, symbol of conjugal bliss, disappearing in the mist. Her pose reflects the meaning of her name, ‘transverse flute’.