makura-e

This name given to erotic pictures in the Edo period derived from the associations of the phrase ‘placing the pillows together’, implying sexual intercourse. Another term was ‘laughing pictures’ (warai-e), with ‘laughter’ being a euphemism for sexual activity. Today the term shunga (‘spring picture’) is often used. The humorous content of some of the prints becomes evident when we eaves-drop on the lovers’ ‘pillow-talk’, which becomes possible when the dialogue actually appears on many of the images.

The explicit nature of this dialogue and the graphic detail of the erotic images need to be understood in terms of the culture that produced and consumed the prints and books. In Edo period Japan sex was considered to be a natural part of human experience to be explored and celebrated for the pleasure it gave and for its positive association with fertility. There was no sense of shame or sin, or any moral code based simply on the involvement of sex; prudery only intruded with the import of Western values after 1868. The propriety of behaviour was judged instead by whether the image reflected correct social relations: whether the liaison involved people from appropriate strata of society, and if it threatened the social hierarchy.

Pillow pictures and pillow books (makurabon) were appreciated for their artistic component. Most major print artists produced erotic designs, which were often among their best work and were afforded some of the most lavish production techniques available. They also had a role in sex education (erotic pictures were part of a bride’s wedding trousseau), and they were used by both men and women from many walks of life as a source of escapism and stimulation, often enjoyed in the company of a lover. In terms of their imagery, sexually explicit shunga overlap with mildly-sensual abun-e (risqué pictures), which give tantalising glimpses of flesh through loosely fitting robes.

Suzuki Harunobu

1724-1770

Lover taking leave of a courtesan

Colour print from woodblocks with blind embossing (kimedashi). Chûban format. 1767.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

The theme of lovers reluctantly parting at dawn often echoes courtly literature. According to The pillow book of Sei Shônagon (Makura no sôshi c.966-1017): ‘A good lover will behave as elegantly at dawn as at any other time … Even when he is dressed he still lingers, vaguely pretending to be fastening his sash … Indeed, one’s attachment to a man depends largely on the elegance of his leave-taking.’ Here a high-ranking courtesan (entitled to a luxurious three-futon mattress) catches at her lover’s kimono jacket (haori) as he prepares to knot its inner tie. Sake for the cup of parting is on the cabinet behind them. The poetic word for ‘parting at dawn’ (kinuginu) means literally ‘these robes and those’, from the habit of lovers sharing clothing as bedding and then separating it at dawn. The man’s jacket has a white geometric symbol repeated on the sleeve, which is one of the crests (Genji mon) identifying the chapters in the classic novel The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari) by Murasaki Shikibu (c.973-1020). References to the novel were often made in this way on prints, and there does not seem to be a specific reference intended here.

The gesture of tugging at the man’s robes to detain him also alludes to a famous Nô play, The Feather Mantle (Hagoromo), in which a fisherman takes an angel’s heavenly feather robe, which she has left hanging on a pine tree by the shore. He threatens to keep it unless she dances for him. After dancing she vanishes into the sky above Mount Fuji, ‘mingling with the mists, fading into the heavens, lost forever to view’. The painted folding-screen in the print almost recreates the setting of the play as part of the room:

’… the snows of Fuji –

peerless … like this spring dawn:

the waves, wind in the pines, the tranquil shore!’

(based on a translation by Royall Tyler)

This print is also encountered with variant blocks used for the wall on the right and for the slopes of Mount Fuji on the screen.

Suzuki Harunobu

1724-1770

Lovers in an interior

Colour print from woodblocks with blind embossing (kimedashi and karazuri). Chûban format. c.1770.

Given by The Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum 1994

For much of the Edo period shunga could not be published legally, and although the ban was not strictly enforced, the names of artist and publisher were usually omitted, as in this example. Most shunga appeared in the discreet form of albums, with a less explicit print chosen for the first illustration.

Although anatomically explicit, shunga are rarely realistic. Physical attributes are often exaggerated and the situations are frequently improbable, sometimes for the sake of humour. Many of the prints recall the flavour of the amorous, and often rather far-fetched, episodes in classical Japanese literature.

The printing effects in shunga can be exquisite, suggesting that they were aimed at connoisseurs who were sophisticated in their appreciation of the subtleties of printmaking. In this case luxuriously thick paper is embossed from the back to swell the volume of naked limbs, and the subtle carving and printing around the woman’s crotch is remarkable. The delicately provocative gesture of the woman’s hand lightly grasping the uncertain young lover’s wrist is typical of Harunobu. A third figure is more usually encountered as a voyeur, and less frequently as a courtesan’s real lover intruding while a client sleeps.

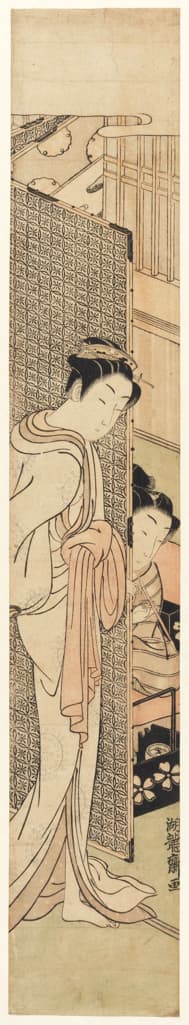

Isoda Koryûsai

active 1766-88

Courtesan returning to her lover

Colour print from woodblocks. Hashira-e format. c.1771.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

A courtesan returning to her lover who waits for her behind the folding screen, smoking a pipe. Her white nightgown parts to show her breast and ankle, while still clinging to her form to emphasise the curve of her buttock and the line of her thigh. The proximity of the lovers’ meeting is subtly suggested by the juxtaposition of their hands - her fingers curl round the edge of the screen and almost seem to touch his hand that holds the pipe. The provocative glimpse of the woman’s body is typical of prints known as abuna-e (risqué picture). The expression was used as early as 1687 in a ‘floating world’ story book (ukiyo-zôshi) entitled Amorous educational pictures (Kôshoku kimmô zui); it defined the quality of tantalising pictures that show only a glimpse rather than revealing all.

This tall narrow format of prints, or ‘pillar pictures’ (hashira-e), was so named because they were hung or pasted on narrow wooden interior pillars (hashira). Koryûsai was particularly adept at exploiting the format, here using the screen to divide the already narrow format into still narrower vertical strips.

Katsukawa Shunchô

active c.1781-1801

A geisha with her lover

Colour print from woodblocks. Aiban format. 1780s.

Given by The Friends of the Fitzwilliam 2012

From the erotic series ‘Customs of the Geisha’ (Geisha no fuzoku). This is a scene in the pleasure quarter. A geisha has been visited by her lover who is impatient to get on with their lovemaking, while she would rather they were a little more discreet and closed the sliding doors first.

The theme of the print is similar to the print by Shunchô below, although the use of colour (extremely well preserved in this impression) is very different.

Him:

‘I am taken by this urge all of a sudden. How can you wait even a little? I feel myself beginning to come even without doing anything. And your soft place is getting wetter. I can’t bear it anymore!’

Her:

‘You are too impatient! It will be terrible if someone sees us, so wait until I close those sliding doors. Oh, this is ridiculous! Let go of me!’

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

Katsukawa Shunchô

active c.1781-1801

A couple kissing whilst making love

Colour print from woodblocks (benigirai-e) with metallic printing. Ôban format. 1780s.

Given by The Friends of the Fitzwilliam 2012

The woman has been interrupted by her lover while smoking a pipe and reading a book. The theme is similar to the adjacent print by Shunchô - the man is eager while his lover would rather wait until evening.

This is a ‘red-avoiding’ print (benigirai-e), using a restrained colour scheme, which enjoyed a vogue in the 1780s. Benigirai-e was formerly supposed to be a response to censorship laws restricting the use of colour, but the government actually condemned such prints as examples of exaggerated taste: they were designed to appeal to sophisticated collectors who appreciated the refined effect of a muted palette.

Him:

‘When I see you lying there I feel so dizzy I’m dazzled. I can’t bear it! And how can you wait, while your soft place gets wetter and wetter? Let’s be quick … come on, come on!’

Her:

‘No, this is no good! I don’t feel right doing it during the day. Wait until this evening. Hey, this is ridiculous! It’s pointless doing that!’

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

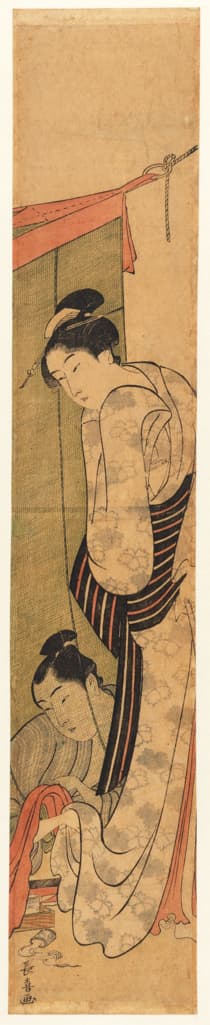

Eishosai Choki

active c.1770-1810

Man lifting the dress of a woman

Colour print from woodblocks. Hashira-e format. c.1794.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

The woman, scantily clad, appears to have knocked over a tea-cup whilst emerging from underneath the mosquito net that usually surrounds a bed. Her lover lifts her dress, ostensibly to prevent it trailing in the spilt liquid, but with erotic overtones that add to the glimpse of her red undergarment and naked leg. Tucked into the opening of the woman’s robe above her sash is a roll of tissues commonly depicted in erotic prints (shunga), where their purpose was to clean up after sex. The implication is that the woman emerged from the bed during a break in their lovemaking.

The provocative glimpse of the woman’s body is typical of prints known as abuna-e (risqué picture). The expression was used as early as 1687 in a ‘floating world’ story book (ukiyo-zôshi) entitled Amorous educational pictures (Kôshoku kimmô zui); it defined the quality of tantalising pictures that show only a glimpse rather than revealing all.

Mosquito nets were a favoured subject because of the opportunity to combine a tour-de-force demonstration of block-cutting with imaginative pictorial effects, contrasting the depiction of figures behind or in front of the net.

Yanagawa Shigenobu

1787-1833

A man with two women under a mosquito net

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Late 1820s.

Bought from the Reitlinger Print Duplicates Fund 2013

From the album of twelve prints known as ‘Willow Storm’ (Yanagi no arashi), although this is a recently assigned title. Shigenobu was for a period a pupil and son-in-law of Hokusai (the marriage was dissolved), although he developed an independent style. This print is a particularly daring design in veiling so much with the mosquito net.

The dialogue reveals the couple planning to involve the sleeping woman in a three-some, which is rare in shunga. It is not entirely clear whether ‘mother’ refers to the women’s mother or to a brothel keeper.

Him:

‘Well, my dear, it’s very nice of you to have brought another woman. Oh no, she’s asleep! How disappointing!’

Her:

‘Wait a minute - you should have been here quicker! She was so tired of waiting after I brought her here that she fell asleep. That’s why you’re finding it disappointing. And anyway, is it really disappointing? She’s showing you a cute place. And she’s going to stay with me overnight as she was feeling rather down after waking ‘mother’ up and causing a big fuss. So, since she’s already made a big fuss, let’s get her to make love with us! [Sounds of moaning] Oh, be quiet! Be quiet!’

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

Yanagawa Shigenobu

1787-1833

Dutch lovers

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Late 1820s.

Bought from the Reitlinger Print Duplicates Fund 2013

From the album of twelve prints known as ‘Willow Storm’ (Yanagi no arashi), although this is a recently assigned title. This print shows a Dutch couple (nanbanjin - or ‘Southern Barbarians’ - originally a term naming Spanish and Portuguese arriving in Japan from the south, but later applied generally to westerners), and in showing them naked having sex it is a unique occurrence within shunga. It was made in imitation of the shading and appearance of European copperplate prints, although no specific model has been identified.

The dialogue is given in mock ‘Dutch’ with translations following in Japanese:

In Japanese it says:

Her:

‘Of all the lecherous men, it is when I see your face that my clitoris jumps up! I am coming without you: please put it in quickly! Oh…oh… When I play around with you like this, I can’t resist!’ This is what the Dutch says.

Also this in Japanese means:

Him:

‘By the standards of our country, I am a lustful person but there is no person as lascivious as you are. You are a beautiful woman and also lecherous, which is a second string to your bow! [literally ‘an iron rod to a demon’, a Japanese saying]. It is very nice when you handle my cock as if it were a rod. I got tired of doing it. I got tired of putting it in. I’ll fondle your breasts and this will bring the desire back. It’s good to enjoy this for a long time and without hurrying. It’s better to do it fifteen times enjoying it than do it thirty times one after another. Oh, I’m aroused again now and I want to put it in again. Once I take it out I always have this problem. Come on, let’s start again’. This is what the text says.

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

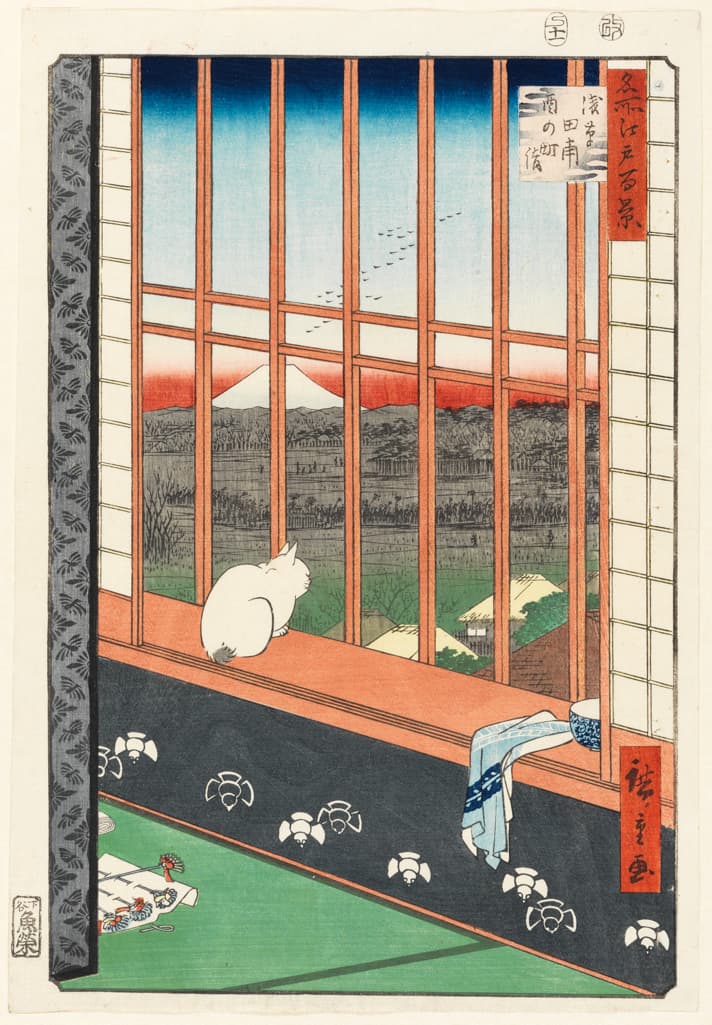

Utagawa Hiroshige

1797-1858

Asakusa rice fields during the Festival of the Cock

Asakusa tambo torinomachi môde

Colour print from woodblocks. Ôban format. Publisher: Uoya Eikichi (Uoei). 11/1857.

Given by T. H. Riches 1913

No. 101 in the series ‘One hundred famous views of Edo’ (Meisho Edo hyakkei), in the section for Winter. Through an opened upstairs window of a Yoshiwara brothel the distant Torinomachi procession can be seen winding its way to the Washi Daimyôjin Shrine. The festival was held on the days of the cock in the eleventh month. Distant figures can be seen carrying bamboo rakes decorated with symbols of prosperity for the year ahead. Miniature versions of these in the form of hairpins are lying on the floor in the room, probably souvenirs purchased at the shrine and brought by a visitor as a gift for the courtesan. This was the busiest day of the year in the Yoshiwara, a day when each courtesan had to take a customer or else pay the fee to the brothel owner out of her own pocket. Lying above the hairpins is a roll of tissues known as ‘paper for honourable act’ (onkotogami), suggesting that sex is in the offing, and on the window-ledge are a mouth-rinsing bowl and a towel.

Is the visitor still here with the courtesan behind the screen? The courtesan might have opened the window and used the bowl and towel after the visitor left; but the tissues have not all been used, and the cat is taking the opportunity to look the other way.

An alternative printing, probably earlier, has more refined printing, including embossing (kimedashi) to emphasise the outline of the cat.

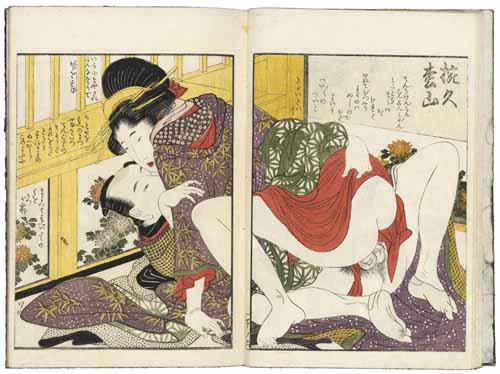

Kitagawa Utamaro

c.1753-1806

On the road: Love songs for the thick-necked shamisen

Michiyuki koi no futozao

Book printed in colour from woodblocks, 3 volumes, hanshibon format, ‘bag’ binding (fukuro-toji), covers painted with gold design, printed title slips ‘numbered’ jô (top) chû (centre) ge (bottom). [Edo] 1802.

Bought with the American Friends of Cambridge University Fund 2007

The frontispiece in each volume depicts a stage puppet with a geisha. All of the illustrations depict ‘fated lovers’ who committed double ‘love suicide’ in stories that evolved into a line of dramas for the puppet and Kabuki theatres called shinjû mono (double-suicide plays). The characters are named on each image and accompanied by text conveying their dialogue, probably invented by Utamaro. Utamaro’s images and dialogue either give more explicit versions of the liaisons that take place in the original play, or they imagine extra sex scenes that were not enacted on the stage. The ‘shamisen’ mentioned suggestively in the title was a three-stringed instrument used to accompany sung narrative (jjôruri) on the stage.

This is a very rare copy of a colour edition of this book using the outline blocks before they were recut for later printings, possibly because of a fire.

Volume 1 Osono and Rokusaburô

Based on recent events, the story of Osono and Rokusaburô was first dramatised in Osaka in 1749 in the play Multi-layered mists and the grasses of Naniwa shore (Yaegasumi Naniwa no hamaogi) and in a different play first performed in 1759, Taihei Chronicles: the Kikusui volume (Taiheiki kikusui no maki).

The geisha Osono is daughter of the proprietor of Fukushimaya teahouse in the Fukagawa unlicenced pleasure district. She has been promised to Chôbei, but he hears rumours that she is pregnant, and notices that she has Rokusaburô’s name tattooed on her arm, a sure sign that they are lovers. Chôbei plots with Kashiku no Omatsu, the daughter of Rokusaburô’s wet nurse, to make Osono take a medication that will make her abort the baby. As part of the convoluted plot that develops around a stolen piece of gold, Osono and Rokusaburô visit Osono’s father, Seibei, on their way to the place where they intend to commit double suicide so that they can be together forever. When they arrive, Seibei is praying for the dead, in a festivity known as obon. He gives each of the two lovers a kosode (short-sleeved robe), which they will wear along the road.

Rokusaburô:

‘When we play around like this, having sex and kissing, even [boring] days such as obon and the first day of the year are not tedious any more. I pay my respects to Seibei, and deal with Chôbei, working hard to protect your reputation. So there’s no one busier. And besides that, there is this lascivious letter…’

Osono:

‘If I make an effort to please Chôbei, he will [pay] for five or more years. But I am against benefitting like that and won’t do it. Stop playing around and put it in quickly!’

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

Volume 2 Osato and Yasuke

Osato and Yasuke appear in the play Yoshitsune and the Thousand Cherry Trees (Yoshitsune Senbonzakura), based on legends surrounding the defeat of the Taira clan. The lovers feature mainly in the scene in the third act at the sushi shop of Osato’s father. Utamaro imagines an erotic development when Osato and the refined-looking and recently hired servant Yasuke are fondly talking about their forthcoming marriage. At this moment Yasuke looks round when he hears Osato’s brother Gonta arriving home (with the intention of asking his mother for money).

Osato:

‘My father said that he will arrange the wedding ceremony with you, Yasuke, tomorrow night. He doesn’t know that we’ve already consummated our marriage like this. Parents are so stupid!’

Yasuke:

‘Shall we bring our bodies together as if we were sushi? I hear the voice of your brother outside the door. I hate him more than anyone else. Your mother and father are fine people, though.’

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

This was the lovers’ happiest moment: later, on their wedding night, Yasuke reveals to Osato that he is actually the Taira general Koremori in disguise, with a wife and child in another province, and asks to be released from his vows.

Volume 3 Matsuyama and Wankyû

Based on real life, the story of Matsuyama and Wankyû was told in Ihara Saikaku’s ‘floating world’ story book, The story of the life of Wankyû (Wankyû isse no monogatari), 1685, and first dramatized on the puppet stage in 1708 in Ki Kaion’s play Wankyû and Matsuyama, the pine-clad mountain (Wankyû sue no Matsuyama), with a Kabuki version premiered around the same time.

On the eve of the Bean-throwing Festival (setsubun), Wankyû’s father discovers that he has been spending extravagantly, throwing gold around like beans, while in the company of the courtesan Matsuyama in Osaka’s Shinmachi pleasure quarter. He disowns his son, and to prevent further scandal, Wankyû is locked up at his father-in-law’s house. Climbing the fence to visit him secretly, Matsuyama falls and is helped by Wankyû’s wife. Stricken by a sense of duty to his wife, Matsuyama breaks up with Wankyû, who subsequently loses his mind and wanders from town to town. Eventually Wankyû recovers his inheritance and is reunited happily with Matsuyama.

Matsuyama:

‘Even [in the age of the gods] when earth and heaven were still undivided, there were, and still are, many superb cocks. But the only one that really surprises when it’s inserted is yours! At last, at last, at last, I feel alive!’

Wankyû:

‘Because of your lavish praise I am having sex like this. I put all my money into you, the ‘Mountain Pine’ (Matsuyama) that goes on forever [lasts a thousand years]! I never forget you, not even for a second. That’s why I’m so confused. And I end up by lifting bamboo leaves [the pattern on her kimono].’

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

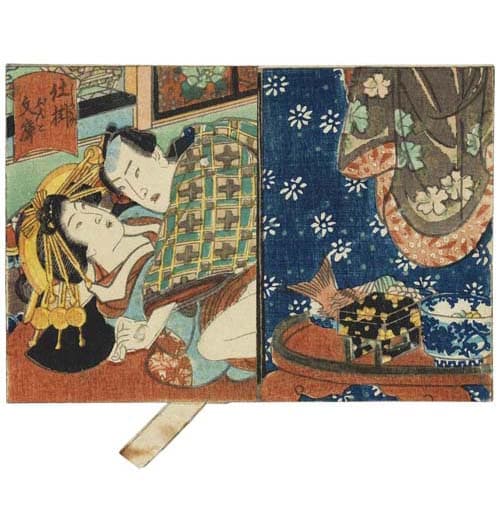

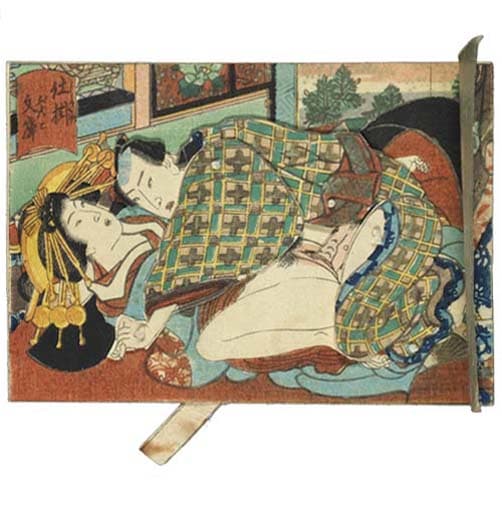

Utagawa Kunisada

1786 1865

Rustic Genji Suma koto

Sumagoto inaka Genji

Book printed in colour from woodblocks with metallic pigment, burnishing and blind embossing (karazuri), 3 volumes, hanshibon format, ‘hybrid’ binding (konsei-toji), colour-printed covers, printed silk title slips, ‘numbered’ ten (heaven) chi (earth) jin (man), colour-printed wrapper (fukuro) with Genji chapter symbols and scenes in shells, with wooden case (chitsu). Author: Ryûtei Tanehiko. [Edo] 1838.

Given by the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum 2013

This luxuriously printed and presented book is an erotic elaboration by the same author and illustrator of incidents from the first 14 chapters of the best-selling serial novel Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji (Nise Murasaki inaka Genji), 1829-42, including the hero’s exile in Suma playing the koto (a type of zither). Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji was itself an updated adaptation of the classic eleventh-century novel, The Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari), adding intrigue, theatrical plot-twists and trend-setting fashions, see two related prints on the Love Stories page.

This version elaborates and makes explicit the sexual element in the hero Mitsuuji’s love affairs. The same author, Ryûtei Tanehiko (1783-1842), collaborated with Kunisada in the late 1830s on several books that eroticised Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji; these were condemned in 1842 under the new censorship policy of the Tenpô Reforms for being erotic and altogether too gorgeous.

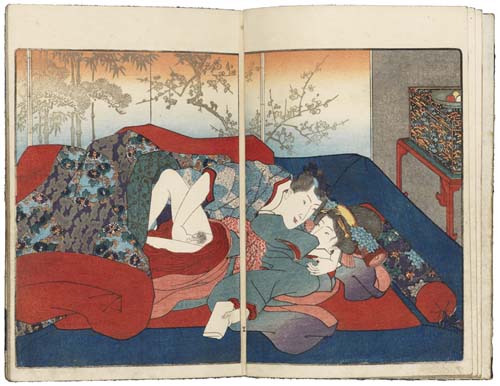

Volume 1

Mitsuuji and the geisha Tasogare in the Misujimachi pleasure quarter in Kyoto. While Tasogare’s mother and Mitsuuji’s retainer slept soundly in the next room, Tasogare put her head on Mitsuuji’s knee and flirted with him. The text continues:

‘Mitsuuji put his left hand on Tasogare’s shoulder and his right hand at the place of her “hidden door”… When he caressed her clitoris, Tasogare moved her body against his and closed her eyes.’

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

This text and image make more explicit the following passage from Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji:

‘Even unrefined mountain people feel the desire to rest for a while beneath beautiful cherry blossoms. Although everyone in the world has that wish, Tasogare could never have expected the high-ranking Mitsuuji to show any interest in her, but that night she slept beneath his love. The two exchanged vows as deep as those made by the lovers who compressed a thousand nights of love into a single night, and their desire to exchange even more vows ended only when roosters crowed at dawn.’

(translation: Chris Drake)

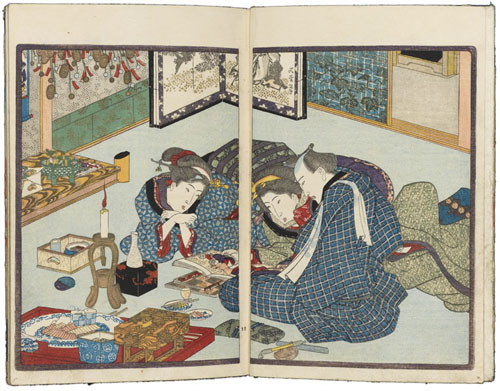

Volume 2

Mitsuuji, in the company of two women, looks at a book with erotic illustrations. Food and drink is only set out for two of them. Mitsuuji’s hand has surreptitiously crept between the legs of the woman in green. There is no corresponding illustration in Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji.

As was usual in erotic books, Kunisada does not sign his artist’s name but uses a pseudonym, Matabei (after the legendary artist Ukiyo Matabei), which appears discreetly as the signature on the painted screen.

The extraordinary range of carving and printing effects used to convey the variety of elaborately decorated and textured surfaces is typical of the lavish production values of this book, and similar luxury editions. Erotic books were by far the most lavishly produced type of book during the second quarter of the nineteenth century, utilizing the most expensive materials and technical effects only otherwise employed in the privately commissioned category of print called Surimono. Luxury erotic books may also have had private sponsors, and would have been an expensive item.

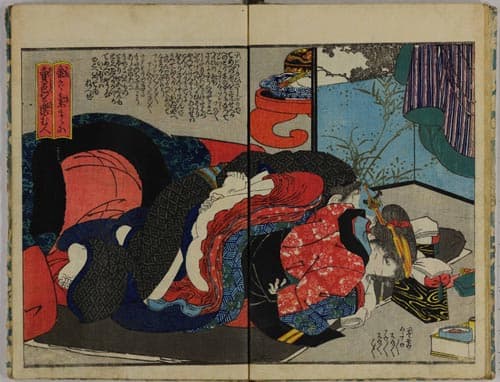

Volume 3

After they are married, Mitsuuji takes Murasaki back to his mansion in Saga. He visits her room in the middle of the night, and invites her to have sex with him, as ‘this is what a husband and wife should do’. She is unwilling, perhaps because it is her first time. Kunisada illustrates a slightly later moment in the text than the scene depicted in Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji (Nise Murasaki inaka Genji):

‘He reached out his hand and pulled at the tightly-closed maezuma [the kimono fastening] to open it’.

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

This depiction also seems to have been inspired by an illustration in the erotic book, Pillow Talk (Ehon makura kotoba), by Kitao Masanobu, dating from 1785.

In later images in this book the couple are enjoying sex, with Murasaki’s initial reluctance gone: ‘she was like a cherry flower blossoming’.

Keisai Eisen

1790-1848

Two aspects of love

Konote gashiwa

Book printed in colour from woodblocks with metallic pigment, burnishing and blind embossing (karazuri), 3 volumes, text by Hanagasa Bunkyô, hanshibon format, ‘hybrid’ binding (konsei-toji), colour-printed covers, printed title slips ‘numbered’ jô (top) chû (centre) ge (bottom). [Edo], 1836.

Lent from the Ebi collection

The literal meaning of the title of this luxurious book, ‘Child’s-hand oak’, refers to a tree that has a leaf with similar sides, used here as a metaphor for alternate aspects of love. The introductory text by Hanagasa Bunkyô (1785-1861) proposes a comparison between the surface (omote) of things and the true meaning that lies beneath (ura). This technique of pointing out what was hidden, ugachi (hole-digging), was common in various forms of gesaku (vernacular playful writing). The twin title-cartouches on the illustrations also contrast ‘surface’ and ‘hidden’ aspects, although this is not consistently maintained throughout all three volumes.

Volume 2 focuses on the pleasure quarter, where the surface appearance (omote) is that women pretend only to be selling love, while underneath (ura) they enjoy it just as much as their customer.

Volume 3 contrasts customers versed in the etiquette of the pleasure quarter with those who are not; and contrasts women who can make even an unskilled customer seem skilled as a lover, with those who cannot. The reader is warned not to get ripped off.

Volume 1

The Lord of Ôgi ga yatsu in Kamakura loves a beautiful woman and this is a scene of their amusement.

The woman sees her lover’s face reflected in the water; he is revealed in person on the next page, as though glancing down at the water on this page. He wears his hair in the topknot made fashionable by Mitsuuji in the illustrated novel Imitation Murasaki-Rustic Genji (Nise Murasaki inaka Genji).

The poem in the sky above the ducks is written in Chinese characters (kanshi):

Mandarin ducks on a pillow –

three sleeping heads.

Kingfishers enclosed within sliding doors –

six legs encroached.

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

Mandarin ducks were a symbol of fidelity because it was believed that they paired for life.

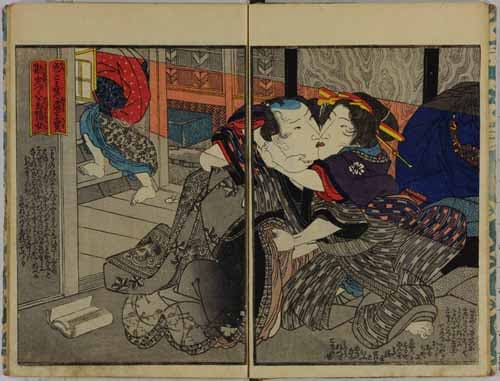

Volume 2

Even while earning money by entertaining clients a woman will escape to visit a lover and show her real feelings.

Her:

‘You took the trouble to come but you chose the wrong time. You shouldn’t visit me when you don’t have business here. My workmate has just passed by. Oh, how mischievous to throw light on us, and you toying with me! Don’t people know you should act appropriately according to the situation? Well, you certainly don’t understand even when it’s right in front of your eyes! Boy oh boy!’

Him:

‘Yes, I do visit you even though I have no business here. Since I have something to say I thought we could take our time, but you are so bad-tempered that things are not going as I wished. But you are making me feel excited. That’s irritating! You don’t let me talk about my feelings for you. How frustrating!’

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

Volume 3

A man who enjoys paid sex by using his money freely.

Him:

‘Is this good? As I’m enjoying your pussy after such a long time, my cock has become as hard as a piece of wood. Yes! … oh that’s good! … Oh yes! … ah! [etcetera…] My messenger must have delivered [to your brothel] what I had entrusted to him, so today I only brought a bit of money with me, which I’ll give you before I go home. As for my usual sex before I come here again [to you], I’ll ask the seamstress [to find someone else]. She’ll make it possible to use a nice room [the seamstress had a room next to that of the brothel proprietor]. Oh! Ah! … yes … I’m coming, I’m coming, I’m coming. Ah … oogh! [etcetera…] … Let’s do it again later. As usual, let’s do it four or five times before tomorrow morning. How do you want me to put it in? A pussy as good as yours is without compare!’

Her:

‘Mmmm! Ah, oh yes!’ [etcetera…]

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)

School of Utagawa Kunisada

c.1860s

The intimate bed

Najimi no toko

Colour print from woodblocks on several cut-out sheets assembled with thread to form an image with moving parts. Shikake-e. c.1860

Lent from a private collection

From the series ‘A collection of tricks’ (Shikake bunko). Trick elements were introduced in erotic books from the 1820s, with hinged flaps for a door or screen that could be lifted to reveal sexual activity beneath. The same idea was developed in interactive ‘trick prints’ (shikake-e), which sometimes had moving parts, as in this example.

This shows the flap lifted. Hover mouse over the tab to move the figures.

On the back is a text with dialogue:

A town populated by love and lovers. One wanders among streets where, beside love, compassion lies with sleeping figures. How prosperous the pleasure quarter is. This is indeed the heavenly kingdom!

Him:

‘I have tried many women here and there, but even a person like me has been captivated by you. First, you are beautiful. Moreover, you are good at flattering me. On top of that your bed is good. That’s why [I’m captivated].’

Her:

‘Well, do you think that I’m like that with everyone?! How provoking you are! There are very few customers that I like as much as you…’

Him:

‘That proves you’ve fallen for me! I shall keep coming here even if it gets me into financial trouble. It’s my style to keep on doing it while I can keep my end up!’

(based on a translation by Laura Moretti)